Long before Emirates emblazoned its name on the world's jetways and Doha became a layover between continents, the skies of the Gulf were carved out by imperial ambition. Aircraft of the Royal Air Force first touched down in the Arabian Gulf as an enforcer of British policy, armed not with bombs alone but with bureaucracy in flight. The RAF's mandate wasn't just to strike, it was to watch, to warn, to wait, and, when called upon, to deliver the power of the British Crown across the vast, volatile lands between the Tigris and the Trucial Coast.

Between 1920 and 1980, a lattice of airfields sprang up in Iraq, Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, and the Emirates, each a node in the great imperial nervous system. These were not mere patches of tarmac but geopolitical statements, asserting British reach in an age when the sun was already beginning to set on the Empire. But as Britain withdrew from east of Suez in the early 1970s, something curious happened. RAF bases became international airports, their wartime supply depots became global commercial logistics hubs. British pilots gave way to Arab air traffic controllers, foreign squadrons replaced by national airlines with ambitions that soared far beyond the bounds of old imperial maps.

This is not just a story of runways and refuelling stops. It's the tale of how infrastructure laid for war became the skeleton of prosperity in peace. Of how imperial necessity begot postcolonial possibility, and of how the echoes of British airpower still linger in Gulf skies, not in force, but in form. This is the story of how the RAF’s forgotten footprints became the launchpads of a modern aerospace renaissance.

Wings Over the Sands (1920–1940)

The story of British airpower in the Gulf begins, as many imperial stories do, not with strategy, but with cost-cutting. In the aftermath of World War I, the British Empire faced an overstretched army, spiralling expenses, and rising unrest across its territories. Nowhere was this felt more keenly than in the newly cobbled-together territory of Iraq, a land forged by fiat at the 1921 Cairo Conference. With the lines from the Sykes-Picot Agreement still wet and Arab revolts simmering, London found itself in urgent need of a cheap means to police the periphery. The concept of air control by the Royal Air Force, championed by Air Marshal Hugh Trenchard was born here. Rather than stationing thousands of troops to maintain order, Britain would administer Mesopotamia from the skies. Bases were established at RAF Hinaidi near Baghdad and RAF Shaibah near Basra, with aircraft like the Vickers Vernon and the de Havilland DH.9As becoming workhorses of regional surveillance and support operations. The method was not without controversy, but from London’s perspective it worked involving fewer troops, faster response times, and lower costs.

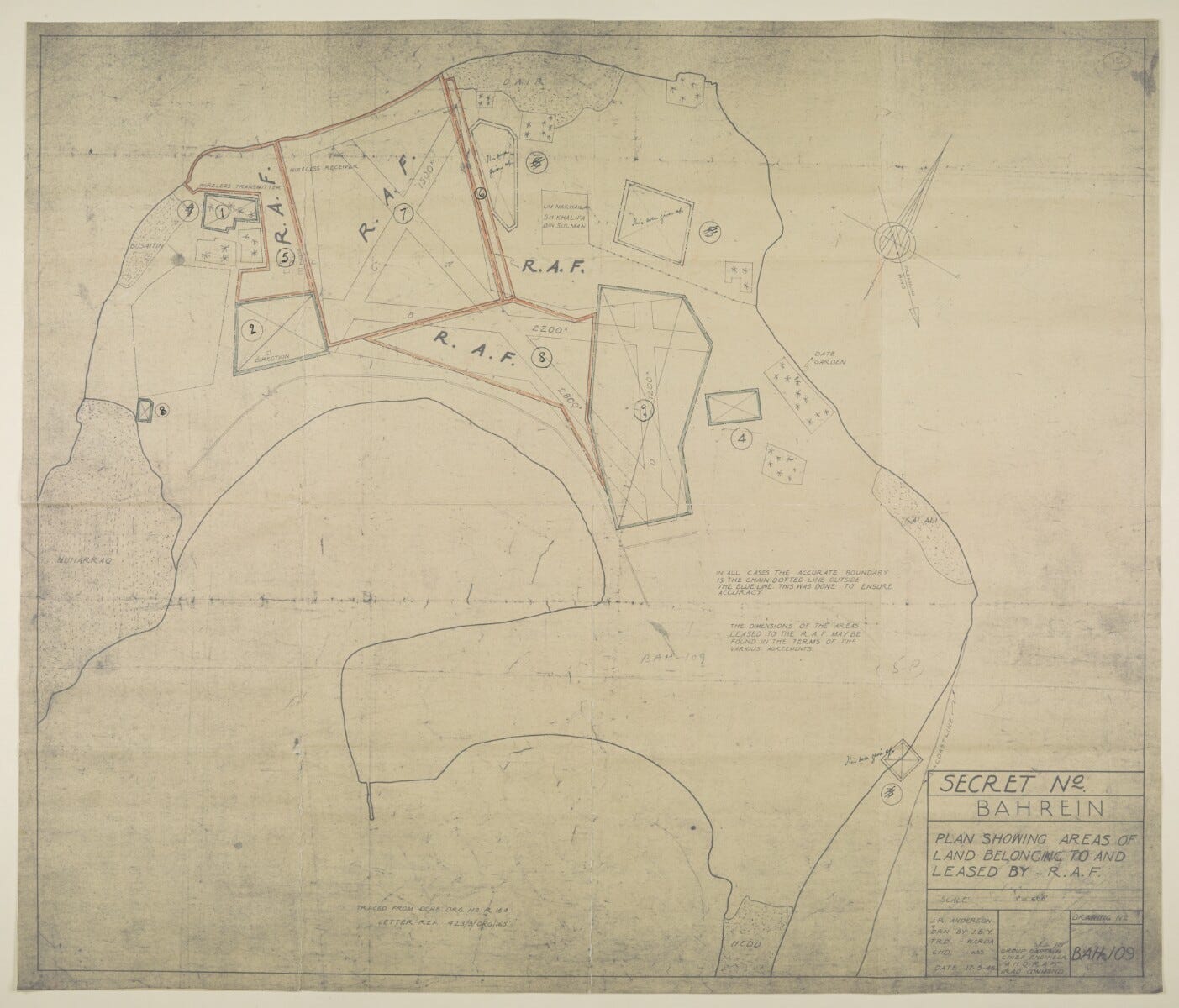

A British withdrawal from Persia in 1920 forced the Empire to began the search for the creation of a new air route to India. On 8 June 1924, three planes left RAF Shaibah for the first official flight to Bahrain. This led to the establishment of an RAF presence on the island, initially operating from a makeshift aerodrome south of the capital Manama before a more permanent facility was developped, one that would grow into RAF Muharraq, a critical link in the imperial air network. Its location, straddling India and the Middle East, proved invaluable for long-range flights and refuelling missions. British officials in the Gulf were interested in the possibility of using Bahrain as a base for any potential flights to Riyadh, the capital of Ibn Saud’s increasingly powerful Sultanate of Najd, which had recently conquered the British-allied Hashemite Kingdom of Hejaz, in a bid to display British aerial superiority and deter his further expansion to the north into Iraq and Kuwait.

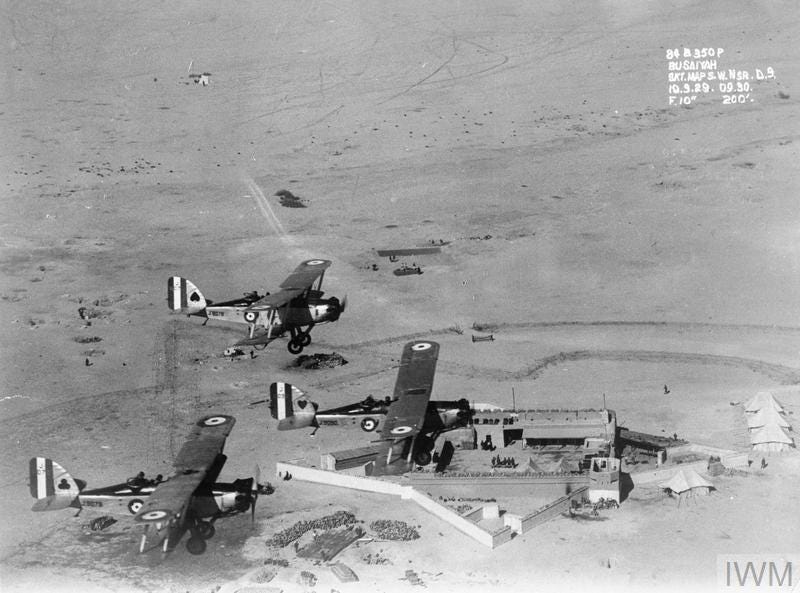

This was realised in late 1927, when RAF assistance was called upon by the Sheikh of Kuwait to defend the state in the face of raids by the Ikhwan, a Wahhabist militia that aided Ibn Saud, who would later be crowned King Abdulaziz of Saudi Arabia, in his conquest of the Arabian Peninsula. DH.9As from RAF Shaibah formed “Akforce” and were dispatched to perform aerial reconnaissance and aid Kuwaiti tribesmen in repelling the raiders. British aircraft patrolled the desert horizon, providing a visible and effective deterrent.

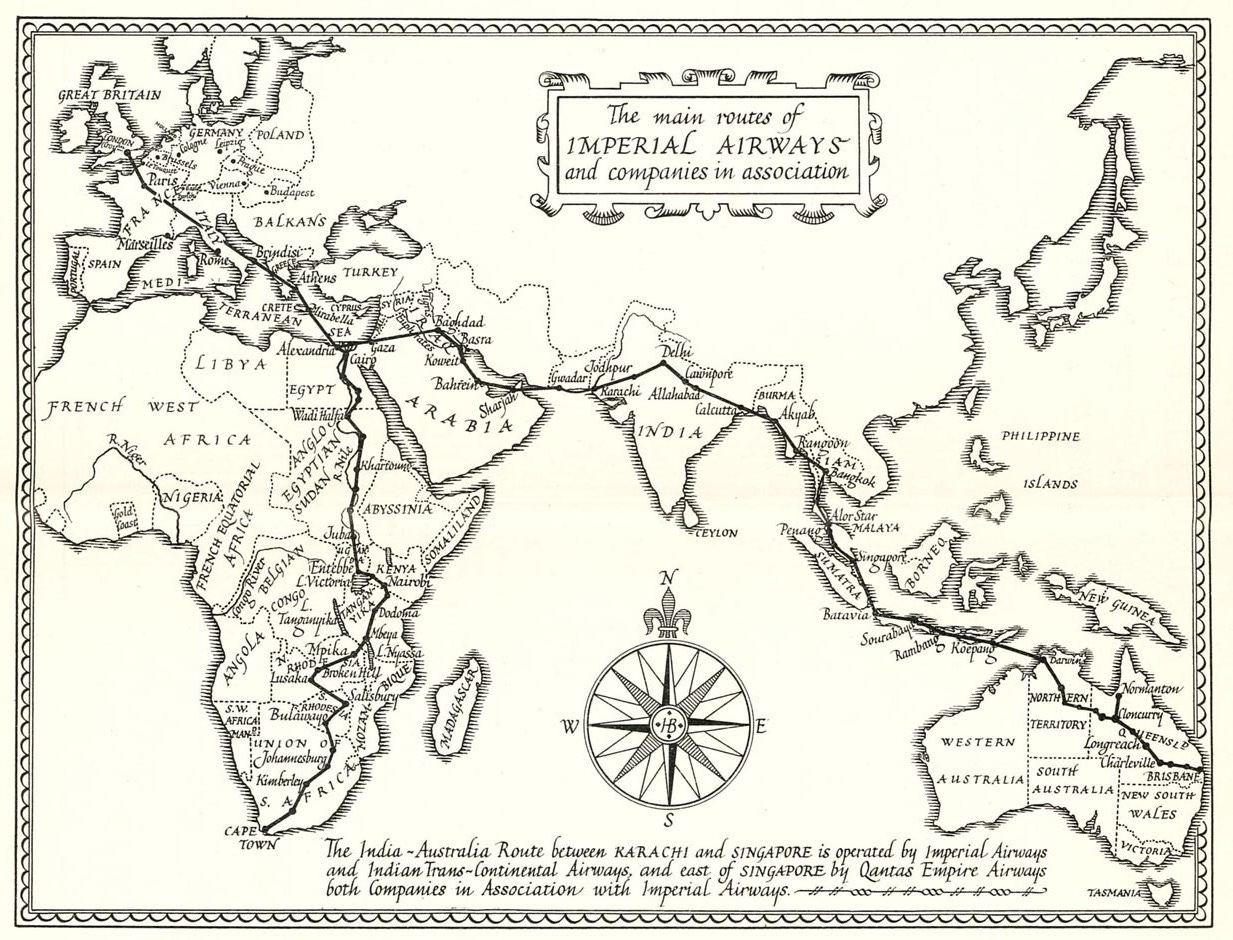

Meanwhile, further down the coast, the Emirates, then the Trucial States on what was once called the Pirate Coast, became key staging posts for Imperial Airways. The most prominent was RAF Sharjah, established in the early 1930s through a treaty with the local rulers. Though modest, the airfield served as a vital rest stop on flights between the Middle East and British India and beyond, a dusty airstrip with global reach. These early decades laid the groundwork for what would become a dense web of British aviation infrastructure throughout the Gulf. What began as a logistical necessity gradually took on a deeper role, shaping not just how the region was governed, but how it was connected to the wider world.

Outposts and Oilfields (1940–1960)

The Second World War changed the calculus of British air infrastructure in the Gulf. What had begun as a string of modest airfields and refuelling stops suddenly became frontline assets in the global fight against fascism. The RAF’s stations, with its geographic centrality between theatres of war (Europe, North Africa, the Indian Ocean) and its proximity to oil, having only three centres of production at the time - Awali in Bahrain, Abadan in Iran and Kirkuk in Iraq, were thrust into the logistical heart of Allied strategy. In Iraq, RAF Habbaniya, which replaced RAF Hinaidi in 1937 as the headquarters og RAF Iraq Command, became infamous in 1941 when it stood alone against a pro-Axis coup in Baghdad. The siege of Habbaniya, where a small RAF force repelled a much larger Iraqi army with a mix of outdated aircraft and improvisation, became a peculiar but potent symbol of British resolve in the region. RAF Shaibah too became major logistics hubs, enabling the British Indian Army to flow westward into Iran and the Levant.

Across the Gulf, the importance of Bahrain’s RAF Muharraq grew rapidly, especially in the wake of an impressive Italian Bombing campaign in 1940 which laid bare the island state’s vulnerabilities. The airfield began hosting long-range patrols over the Arabian Sea and acting as a transit node for British and Commonwealth forces heading to the frontlines in India and Burma. Perhaps the biggest contribution of the Khaleeji states to the Allied War effort came in the form of the Gulf Fighter Fund, where over £60,000 was raised by the people of Bahrain, Kuwait and Oman for the purchase of atleast 11 Spitfires, each emblazoned with the name of its donors in English and Arabic - 6 bore the name Bahrain, 3 with Kuwait and one each with Muscat and Oman. The news that Bahrain was buying Spitfires for the RAF prompted threats by the Italians of further air raids, although thankfully these never materialised.

Even as the war ended in 1945, British forces in the region did not demobilise. By the late 1940s, the Cold War had begun, and with it came the strategic obsession with the Middle East as a bulwark against Soviet expansion. Furthermore, the discovery of major oil reserves in Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, and Abu Dhabi raised the stakes. The RAF’s remit shifted from mere presence to protection, of pipelines, of ports, and of pumping stations. With American oil companies investing heavily in the region, Britain aimed to retain its influence through military infrastructure, positioning airfields near oil terminals to reassure allies and deter rivals.

This was the era of the Baghdad Pact of 1955, with rising British air activity in Oman with the opening of RAF Masirah, and deepened overflight arrangements with the Khaleeji sheikhdoms. Airpower was no longer just a tool of war, it was a symbol of who could safeguard the energy arteries of the world. The aircraft themselves evolved too as the lumbering biplanes of the 1920s gave way to the Canberras and Vampires of the postwar RAF. These new machines flew faster, further, and with a message: the Empire may be fraying at the edges, but it still flew the Union Jack overhead. But change was coming as Arab nationalism simmered and the Suez Crisis of 1956 would be a bitter reminder of limits. In the skies over the arab world, jet engines were whispering that a new age of power, and perhaps of withdrawal was about to dawn.

Winds of Withdrawal (1960–1980)

By the 1960s, the writing was on the wall. Suez had shattered illusions, the Sterling had stumbled, and Britain reluctantly began preparing for a world where it could no longer afford to police east of Aden. But even in its final decades, the RAF in the Gulf didn’t simply pack up and go. It managed an extended balancing act, projecting strength while quietly disengaging. When Iraq’s military ruler Abd al-Karim Qasim, who seized power by murdering the Hashemite King Faisal II in 1958, laid claim to the newly independent Kuwait in 1961, treaty bound HM’s Armed Forces responded within days. Operation Vantage saw Hawker Hunters from RAF Muharraq land in Kuwait alongside Royal Marines from the commando carrier HMS Bulwark, deterring an Iraqi invasion without firing a shot. Steps were also taken to strengthen the Kuwaiti Army and create an Air Force of its own, marking one of the last great acts of British imperial airpower.

In the 70s, as military infrastructure transitioned out of British hands, many RAF-built airfields found second lives. The runways at Muharraq became Bahrain International Airport, while RAF Sharjah was handed over in 1971 and eventually developed into Sharjah International Airport, serving civil and cargo aviation needs. British Overseas Airways Corporation (BOAC), the heir to Imperial Airways, began operating modern jets into these ex-military fields, from VC10s to Concordes. In 1976, Bahrain became the first and only Gulf stopover for Concorde’s London–Singapore route, a poetic endnote for an airfield born out of empire, now whispering with supersonic elegance.

Yet not all commitments ended, as seen in Oman, where Britain doubled down, albeit more covertly. RAF detachments supported the Sultan’s Armed Forces during both the Jebel Akhdar War and the Dhofar Rebellion, Cold War-fueled insurgencies backed by Egypt’s Nasser and the communist aligned South Yemenite regimes. Though RAF aircraft weren’t always on the front lines, British pilots, advisors, and "loaned" assets played a decisive role in turning the tide in the Sultan’s favour by the late 1970s. British helicopters, in particular, became lifelines for remote garrisons in the forbidding plateaus. This period also saw the expansion of RAF Masirah with British assistance, to serve both military and emergency civil aviation needs. It soon became a forward operating base for British maritime patrols over the Strait of Hormuz and a fallback in case of Iranian or Soviet expansionism.

From Camouflage to Commercial (1980–2000)

By the 1980s, the Union Jack no longer flew over the Gulf’s airfields, but its imprint remained, etched into the tarmac and control towers of former RAF outposts. What had once been military bastions were being steadily absorbed into the region’s expanding civil aviation landscape. Runways laid for Wellingtons and Lightnings now welcomed Tristars and 747s, and the radar blips no longer marked squadrons, but scheduled arrivals. This was the era when Gulf civil aviation quite literally began to take off, as the Khaleeji states, newly wealthy from oil, saw aviation not just as a necessity but as a symbol of modernity.

Gulf Air, which traces its roots to the 1950s formed with British support, matured into a regional powerhouse, and new national carriers like Emirates took flight, initially borrowing not just planes but flight crews and operational know-how from their British and Pakistani allies. Etihad and Qatar Airways were still on the horizon but gestating in this era. Meanwhile, as the Union Jack came down from Gulf barracks, it was raised symbolically on aircraft tails instead, in BOAC liveries and later British Airways, maintained its presence, retracing the ghost lines of Imperial Airways but now arriving at terminals staffed by customs officers in thoubs and ghutras.

But the transformation was not solely commercial. In the shadow of the Iran-Iraq War (1980-88) Gulf airfields began quietly receiving upgrades, with longer runways and hardened aircraft shelters, not for British aircraft this time, but for their own nascent air forces and American partners who were “just visiting”. Though independent, the Khaleeji States maintained defense agreements with Britain, and occasionally hosted British advisors or maintenance teams. When Saddam Hussein marched into Kuwait, fulfilling Iraq’s decades-long desire of acquring the Arab state in 1990, the Gulf’s old RAF-built airfields were thrust back into military relevance as Tornadoes and Buccaneers returned to Muharraq. The past had returned with a vengeance, as the very infrastructure once laid down for colonial oversight now enabled coalition liberation. As the century drew to a close, the airfields of the empire had been reborn and repurposed. Camouflage gave way to concourses, and hangars once echoing with the whine of jet engines now hummed with the clatter of duty-free trolleys.

Conclusion: Shadows and Skylines

Today, few passengers boarding a flight in Bahrain or Dubai know that their journey begins on airfields once plotted by British hands, built with imperial purpose, and defended through world wars and rebellions. The duty-free perfumes, gleaming jetways, and high-speed runways are monuments not only to economic ambition but to the lingering ghost of Empire, the contours of that military legacy remain beneath runways now lengthened for A380s, behind terminals wrapped in glass and gold, in the very logic of airspace and logistics that shaped the Gulf’s ascent into the jet age. And yet, history has a strange habit of folding back in on itself.

The RAF’s legacy in the Gulf is not one of conquest alone, nor merely retreat. It is a story of adaptation, how imperial infrastructure sowed the seeds of sovereign capability, how the blueprints of empire became the launchpads for independence. The very act of flying which was once the preserve of colonial patrols and imperial route maps became the Gulf's greatest engine of globalisation, modernity, and connectivity. In recent decades, as regional air forces mature and civil aviation becomes a cornerstone of national identity and soft power, many Gulf states have found themselves returning to the airfields their former protectors once called home, not as subjects, but as sovereigns. Muharraq, Masirah, Thumrait, Al Ahmadi, Al Minhad: names once marked on RAF deployment maps are now nodes in Gulf defense and logistics strategies. The airfield that was once a tool of foreign control, has now become an instrument of regional autonomy.

This, perhaps, is the RAF’s final and most unintended legacy in the Gulf, not the endurance of Empire, but the infrastructure of its afterlife. Where once Spitfires launched to patrol imperial oil routes, now Emirates fleets take off to connect Dubai to the rest of the world, and Typhoons fly not under British command, but in Saudi or Qatari liveries. The shadow of the Union Jack lingers, not as a ghost, but as a scaffold. The skies of the Gulf, once the domain of empire, are now filled with the wings of its heirs.

This is a superbly written, perceptive and thought provoking article.